|

Como ha quedado sola la ciudad populosa

La grande entre las naciones se ha vuelto como viuda, La señora de provincias ha sido hecha tributaria. Amargamente llora en la noche, y us lagrimas estan en sus mejillas. No tiene quien la consuele de todos sus amantes Todos sus amigos le faltaron se le volvieron enemigo. The city destroyed by war sits alone, Once full of people, A great city among the nations. Now she weeps alone in the night with none to comfort her. Her young are crushed and burnt with fire. Her buildings have become rubble. Only sorrow remains. Remember what has happened in a city destroyed by war, the once beautiful city, a gem among the cities of the earth lays in ruins. May we who sleep peacefully in our beds Light a candle that illuminates justice May we who do not fear hunger Set a table where everyone is welcome and no one is afraid May we who walk the streets under a blue sky Take actions that repair the harm quickly in our day. Amen.

0 Comments

I begin with gratitude. Lilacs, vegetable gardens, ancient sugar maples, a porcupine sighting, sunny weather and spring’s emerald canopy graced my eleven day tour in Western Massachusetts and Boston. A big shout out to Woolman Retreat Center, Ollie Schwartz, Darla Stabler, Earnest Vener, Liat Melnick, Joshua Blaine, Rabbi Leora Ableson, the Jewish Liberation Fund and my dear friends Rebecca and Carolyn for the considerable effort it took to make a six gig tour feel like a work vacation!

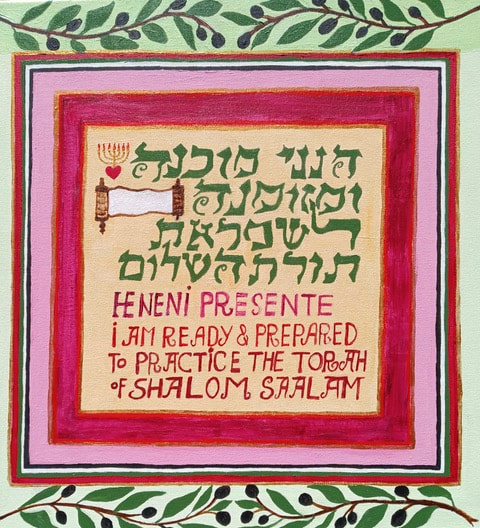

The L’Shem Kedushat retreat brought together queer Jews who are engaged in learning how to process and create diaspora Torah scrolls. I was especially impressed with the way people across the spectrum of attitudes and beliefs about Palestine/Israel and Jewish chalacha created a loving and accepting environment in pursuit of learning how to prepare Torah scrolls from fleshing the animal to getting it ready to be written upon. My role was facilitating Jewish dance, sharing circles and of course, telling stories.These cultural/artistic components of Jewish tradition helped us forge a Mishkan at Woolman Retreat Center in Deerfield, MA. It was delightful to stay at Woolman in order to welcome another cohort of aspiring and veteran Jewish storytellers for a two day retreat. Each person workshopped stories that spanned long jokes, biblical and rabbinic folktales, Hasidic tales and personal accounts. In particular, we were moved by Jules Pashal’s story of a young girl’s struggle as a fat activist in ways that lifted up their beauty and agency and concluded with an image of a bird flying over their body floating effortlessly in a pond. Such an expansive and healing tale. After a week immersed in people seeking to expand their Jewish artisanship skills, I headed to a sold out performance in Northampton of Magida on Sacred Ground. Moving on to a wedding at a Jewish summer camp for the weekend, I was moved once again to realize how important it is to so manyJewish people that recognition of the genocide of Palestinians is part of everything we do during Jewish ceremony and gathering times. Boston was also wonderful - especially being in a multi-faith community working at building the movement for interfaith solidarity with Palestine. I am grateful for the interest in Replanting Seeds of Jewish Revolutionary Nonviolence as a path forward. Jewish storytelling in a shomeret shalom framework of values was a dynamic success. Storytellers workshopped beautiful stories and learned the art of the craft through performance opportunities. Members of Patreon and the Guild will have access to resources provided by Guild subscribers to Patreon and the Jewish storytellers google group from August - December2024.  The Pilgrimage Holiday Shavuot celebrates the giving of Torah. In June 2024, when Israel is committing genocide and Netanyahu is quoting scriptures in Hebrew to assure his voters that apart from a temporary ceasefire to return hostages, the genocide will continue, how do we read Torah? Clearly there are sections of the bible which are genocidal. We cannot ignore violent biblical passages that provide fodder for Israeli state brutality. How do we counter and resist the genocidal and supremacists parts of Torah? A shomeret shalom adopts rabbinic and folk traditions that reject the violence of the bible by imposing an interpretive framework that emphasizes peace, active love, upholding human dignity, pursuit of equity and nonviolence as core principles of Torah. When use of the Torah causes harm, we are instructed to actively repair the harm in ways that lead to the end of harm and the establishment of healing peace. According to Hasidic Masters, the ultimate purpose of Torah is “to make peace in the world…this is the function of Torah: to introduce a unity of peaceful purpose to the diverse forces and peoples of creation, uniting them all in the harmonious endeavor of serving the divine objective:the establishment of peace.” As a shomeret shalom, I feel accountable to the harm being perpetrated in my name by those who have weaponized torah and turned it into a document of Jewish supremacy. As a counter measure, I devote my actions, time and resources to organizing for freedom through movement building to end the genocidal violence being waged against the children of Palestine in the name of Jewish people.Stopping genocide is in our hands. On Shavuot, the holy day devoted to the study of Torah, a shomeret shalom turns to this question: Is learning/study greater or are deeds greater “Rabbi Tarfon answered, ‘Deeds are greater.’ Rabbi Eliezer responded, ‘Learning is greater.’ Then someone else responded to both of them and said, Learning is only greater if and when learning leads to deeds.” (BT Kiddushin 40b) תלמודגדול או מעשה גדול נענה רבי טרפוןואמר מעשה גדול נענה ר"ע ואמר תלמוד גדול נענו כולם ואמרו תלמוד גדולשהתלמוד מביא לידי מעשה Many cities throughout Turtle Island and the world are manifesting interfaith coalitions in pursuit of stopping the genocide of Palestinians by Israel and the US. I’d love to hear about your citiesi nterfaith Ceasefire coalitions. In the Bay Area, our interfaith network is demanding Senator Alex Padilla use his voice to stop the forced starvation and killing of children. In February 2024, Senator Padilla voted in favor of additional $14 billion for arms to Israel, on top of the $3.8 billion US provides to Israel annually. He also voted against Senator Sanders’ resolution that would have asked the State Department to investigate if any human rights violations occurred using US equipment in Israel’s military campaign. Targeted nonviolent campaigns against individual decision makers is critical at this time. Campaigns target an individual decision maker by making an achievable demand. Campaigns are a series of escalating tactics until a win is achieved ,in this case: Stop Arming Israel with our tax dollars! MAGID 5784 All Eyes on Rafah

It is written in the torah diverse multitudes left mitzryim, diverse multitudes resisted oppression together grassroots ruby rousers made beautiful trouble inside the house of the oppressor, defiant doulas refused to cooperate with the hands of death. They had their own plans. The diverse multitudes stood at Sinai. The exodus story was never about one people, it was always about a universal common cause, pushing together against freedom’s gate shouting to the rest of the world and each other, ‘Open, open the gates of freedom. Do you see us? We are human beings.’ Like the people of Gaza, watching their children die and the shores of the red sea seem far away, and they have already walked and walked like Mother Hajar who ran from place to place With her dying child in her arms, crying out. The divine heard her cry and water rose from the ground under her feet. But, Israel has turned off the tap of life and there is no water to drink, No food to eat, no safe place to sleep, no sanitation, no medicine, no rest from the smell of death. In our name, the Mashkheet stalks the land of the the innocent and Israel has become a destroyer of worlds, Creator of an assassination zone, a death camp, a ruined world, Where no child is safe. To what can this be compared: to the ancient oral narrative that sparked an uprising, as our ancestors tell it, as it was passed down and came to rest in Pesikta De Rebbe Eleazar, A young mother named Rachel bat Shutelah was one of the poor Hebrews forced to gather and mix straw and mud to make bricks for the granaries of Pharaoh. The coarse stubble pierced their heels, mingling their blood with clay. A task master with a hard heart beat Rachel without mercy, even though birth pangs shook her body and she cried out in labor. As the rod fell upon her back, Rachel bat Shutelah’s infant child fell from her womb into the mud and drowned. The defiant doulas and their guardian angel pulled the child from the mud and began keening and “Shekinah heard our cry, saw our affliction, our misery, our oppression,” and the time of freedom was soon upon us. Nisan 5784, we step into the task of defiant doulas And refuse to turn away from the cry of the people of Gaza, Tonight we consecrate the spirit of intifada Intifada born in the desire of liberation from oppression Like Miriam who was called Puah because of her defiant voice We unleash the roar of solidarity’s thunder, loud as the crashing waves of the sea upon the shore. We pledge our faithfulness and will not surrender our resistance until Palestine is free from the river to the sea. Tonight, renew the ancient spirit of the mixed multitudes singing open the waters of the sea, so everyone can pass through. Palestine Solidarity: A Monthly Reflection & Shomeret Shalom Direct Action Now the world has been turned upside down amidst the grief and overwhelm. You can support humanitarian aid to Gaza by making a donation to the Middle East Children’s Alliance . Donate Here to Support the Children of Palestine Art from Al Far’a Refugee Camp near Nablus supplied by a near by spring of water. The drawing gives witness to a former torture center opposite the Refugee town that was transformed into a youth center. Storyteller Legacies: Reckoning with Catastrophe My deepest condolences to those of you who are grieving family and friends brutally killed when Hamas murdered 1400 civilians in Israel and took over 200 people hostage. I am sending love to those of you grieving family and friends brutally murdered by the State of Israel’s horrific bombing campaign and settler rampage in Gaza and the West Bank. Over 11,000 Palestinian civilians have been killed, more than 4000 of them children who have no blankets, no food, no water, no beds, no parents, no safety. There is little comfort one can offer in the face of such extreme anguish except to demonstrate loving solidarity in ways that prevent and put an end to more violence. Read the rest of the scroll by subscribing on Patreon Rabbi Lynn speaking at a rally at the final immigrant detention center stop on the Pilgrimage to Heal our Communities in Cali In the News Jewish Nonviolence Can help Guide our Path Forward, Waging Nonviolence At the end of our pilgrimage I was given the honor to share about the links between colonial settlerism in the US and in Israel, and the deadly impact it has. It was truly amazing to be in the presence of so many fabulous front line organizers. Now is the time to build our movements for just change. Listen to my Pilgrimage Rally Speech Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb speaks at the Interfaith Challenge to Protest Curfew in New York in 2015

Gottlieb is celebrating 50 years as a rabbi this September, The Forward After 50 years, pioneering female rabbi is still practicing peace — and protesting Lynn Gottlieb — one of the first women ordained as a rabbi in the U.S. reflects on her activist career — with no regrets. Read more here. Hanooka Book: All of Us in the Light Now is a key moment to choose the meaning of our heritage: Who are we? Stalkers of hatred and war or pursuers of dignity, peace and equity for all? Who will we become in the face of injustice? Wielders of suffering & violence or fierce devotees of revolutionary nonviolence? My Hanooka Book renews traditional Jewish dedication to revolutionary nonviolence. The book rejects Macabean warrior narratives as the path to safety and lifts up 'soul force’ as a prevailing energy that brings justice, healing and joy. This Hanooka, kindle flames each night that illuminate beautiful resistance and peacemaking from the torah of nonviolence. You’ll receive 45 hand-drawn pages filled with stories, games, songs and blessings from global Jewish folklore and R. Lynn’s pilgrimage journeys. Enjoy colorful illustrations and a unique Shomeret Shalom perspective forged over a lifetime of engagement on the front lines of activism for a just world. Order Here! For the sake of our children: A Monthly reflection on PalestineGaza City, 2001. A elder Palestinian woman stands on a chair in her tiny living room kitchen in Gaza City, raises a pointed finger and tells us about her experience of the Nakba of 1948. “We fled against our will. Everything was ripped away from our hands. We left everything behind. Most of you can’t know what that feels like, everything ripped away. Then, during the Intifada, Yitzhak Rabin told Israeli soldiers to break our children’s bones.” Tired from the emotion, she sits down and tells us what her life is like, and serves us tea. Gaza 2023. I pray the woman who hosted us in 2001 is not living through the current nakba, a catastrophe more terrible than ever before. Families flee the bombs but there is no safe place. People wait for death. Refugees robbed of their last scrap of shelter, hold children covered in ash as they run to no where. No manger awaits them, no resting place relieves their sorrow, no red sea opens, no miracle angel appears before them. Death rules their kingdom, raining fire, scorching skin, breaking bones, consuming innocent life without mercy. In solidarity with the people of Gaza, the people of Bethlehem cancelled their public ceremonies around the Christmas Tree in Manger Square. They will neither turn on the lights of the tree, nor host posadas on Star Street. Christmas is all about peace on earth and good will to humanity. In the town of Bethlehem, Palestinians who safeguard Sheppard’s field, the birth of a child represents hope for the world, accompanied by a message of nonviolence as the divine hope for humanity. In Jewish tradition, the people are given torah after they pledge to teach their children about the Way of Peace. In Islam, each child is a gift from Allah and there is a duty to protect them from harm. If we don’t fiercely protect children across all bars, walls and borders with the instruments of peace, we have lost our religious purpose. Now is the time to grasp even more tightly to revolutionary nonviolence and the power of collective nonviolent action to usher in a time of permanent ceasefire and peace. Donate Here to Support the Children of Palestine Storyteller Legacies: The Goddess’s Descent

Tevet is the season of winter in the northern hemisphere and stories about the journey of the goddess to the underworld. The Mesopotamian legend about Goddess Inana is the oldest written version of this tale. Inana puts her ear to the ground to discern the wisdom of the earth and descends into the netherworld to see what lies below. Perhaps she hears the cries of her sibling beneath her feet. The journey below is not an easy one. At each of the seven gates that lead to the nether world, Inana must surrender one more item of her seven pieces of regalia: headdress, necklace, breast plate, bracelets, sash, lower garment, and foot wear, until she is standing naked before her suffering sister, Ereshkigal who has been raped by the Bull of Heaven. Eventually, Inana is able to return to the realm of life by wielding the power of empathy she offers her suffering sibling. From one view, the layers of regalia that Inana removes in her descent to the truth symbolizes the layers of denial we have to shed in order to stand before the truth of Palestinian suffering. What pieces of cherished truth prevent us from full empathy with the Palestinian tragedy? What fear do we hold that prevents us from fulling understanding the plight of our siblings. Just as we ask others, so to we must shed the armor that prevents us from choosing love over fear. When we act together to prevent and dismantle harm, a return to life is possible. As we continue to inhabit the chaos of militarism, Inana’s story teaches us that healing depends upon our choice to put our ear to the ground, witness the truth telling of womyn and children on the front lines of injustice and war, gather our courage and determination in order to move together in the actions we take to end the culture of war. Movement toward life depends on our empathy with the life of every single person across all bars, walls and borders quickly in our day. Read the rest of the scroll by subscribing on Patreon Palestine Solidarity: A Monthly Reflection & Shomeret Shalom Direct Action Now the world has been turned upside down amidst the grief and overwhelm. You can support humanitarian aid to Gaza by making a donation to the Middle East Children’s Alliance . I created the portable altar above for two High Holiday events with Chavurah for Free Palestine in Oakland: A ‘Cast Out the Sins of Zionism Tashlikh’ and a Yom Kippur vidui for the sins of Israeli Apartheid. At Tashlich, in solidarity with Palestinians who are denied access to the sea and subject to massive water theft by the Israeli State, we tore up Israeli bonds in front of the Israeli bond office and put the torn up shreds into a pot with water and Palestinian sage given to me by Daoud Nasser of the Tent of Meeting near Bethlehem. I created a portable paper mache teshuvah altar for the ongoing sins against Palestinian. Your community can sign the Apartheid Free Pledge here: https://afsc.org/apartheid-free-communities. Storyteller Legacies: Celebrating Cultural and Spiritual Continuities

Thank you for supporting my work to train new generations of storytellers, ritual artists and cultural workers committed to liberatory practice. Here is a storytelling thread that ties the generation of Miriam the prophet to contemporary Jewish womyn’s style of celebration of the New Moon and other ceremonial events. New Moon In the biblical period, musician storytellers, ritual workers and keepers of the Mishkan welcomed the new moon by setting up a new moon altar, feasting and singing songs to the moon. Patriarchal expressions of Rosh Hodesh happen in synagogue are a pale shadow of what once was. Adding more words, ie the ‘yaaleh veyavo’ prayer in the Amida prayer erases this once vibrant expression of the centrality of the new moon in Jewish life. On the other hand, womyn’s communities across the Jewish world have observed the new moon by ceasing work (as they do on Shabbat), feasting, singing, making ritual and telling stories throughout the millenium! Perhaps this is the reason religious Jewish men observe Rosh Hodesh as a fast day since their wives do not cook for male members of their families on RH. In the early 1970’s Rosh Hodesh spaces became an important site for feminist cultural workers to transform Jewish life. In my work as a young rabbi, I deployed RH as a way to open the door to innovation, storytelling, and reclaiming centrality for Jewish women’s diverse histories in hundreds of Jewish communities. The picture which shows N African Jewish women celebrating RH Tevet is a retweeted image from Zecharia Shar’abi (Yemenite tradition). The occasion is Eid al-Banat Festival of daughters, celebrated by Jewish womyn from North African communities. Ashkenazi communities call this RH: Day of Judith. Both occur during Hanooka. Wishing you peace in the language of your heart, Rabbi Lynn Photo taken in Hebron in the Jabbar’s make-shift tent after their home was destroyed. 1998 Fasting and Feasting are linked in Jewish ritual time. A brief period of fasting often precedes Jewish life cycle and holiday ceremonies to give us space to focus our hearts and minds on unhealed wounds within self and community before we enter the period of festivities.

Rituals of fasting and reparative action before festival time remind us that we are not permitted to enjoy the cup of celebration without first acknowledging what remains unhealed. The Fast of Esther is part of this tradition. How shall we observe the Fast of Esther this year in 5783? What harms do we need to acknowledge before entering the joy of Purim? Since the rise of the Israeli state, followers of Zionism have used Jewish holidays as weapons of harm deployed against Palestinians. Purim is a case in point. Since its origins more than two millennium ago, Purim has been celebrated as a time of clowning around and imbibing alcohol while listening to a raucous rendition of The Scroll of Esther. The biblical farce about gender and Jewishness in the diaspora originated in Persia and was mostly likely inspired by local spring festivals. The story about a Jewish orphan who becomes Queen consort to the all powerful King Ahashverosh is a fairy tale. In her position as queen, Esther, aka Hadassah, foils a murderous plot by the king’s evil advisor Haman to kill all the Jews living in the Persian Empire. Like many fictional tales from 1001 Nights to Star Wars, the villain’s plot is turned against him and he ends up suffering the terrible fate he planned for his enemies. Hubris is the downfall of the dastardly. The custom of making noise every time Haman’s name is mentioned in the story originates in his identification as a descendant of the biblical account of Amalek, a group of mercenaries known for their extreme cruelty. This association is a way to emphasize just how evil Haman is. In response to their heartless actions, a divine command is issued to blot out the name of Amalek. Jewish people act out that commandment by making noise when Haman’s name is mentioned during the reading of the megillah. Here’s the biblical text about blotting out the name of Amalek: זָכוֹר, אֵת אֲשֶׁר-עָשָׂה לְךָ עֲמָלֵק, בַּדֶּרֶךְ, בְּצֵאתְכֶם מִמִּצְרָים אֲשֶׁר קָרְךָ בַּדֶּרֶךְ, ויְזַנֵּב בְּךָ כָּל-הַנֶּחֱשָׁלִים אַחֲרֶיךָ--וְאַתָּה, עָיֵף וְיָגֵעַ; וְלֹא יָרֵא, אֱלֹהִים וְהָיָה בְּהָניחַ יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ לְךָ מִכָּל-אֹיְבֶיךָ מִסָּבִיב, בָּאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר יְהוָה-אֱלֹהֶיךָ נֹתֵן לְךָ נַחֲלָה לְרִשְׁתָּהּ--תִּמְחֶה אֶת-זֵכֶר עֲמָלֵק, מִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמָיִם; לֹא, תִּשְׁכָּח . “Remember (zachor) what Amalek did to you on your journey, after you left Mitzryim . How, undeterred by ‘fear of God’, he surprised you on the march, when you were famished and weary, and cut down all the stragglers in your rear. Therefore, when Adonai Elohekha grants you safety from all your enemies around you, in the land that the Adonai Elohekha is giving you as a hereditary portion, you shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven. Do not forget!” Deut. 25: 17-19 This passage is read in synagogue on Shabbat Zackhor, The Sabbath of Remembrance, which falls on the Shabbat before Purim. The ‘blotting out’ of Haman was performed, not with a sword, but with noise makers while most of the revelers were inebriated. No one in the rabbinic tradition thought a person should blot out the name of Amalek by literally going out and killing descendants of Amalek, as the following texts covering a period of two thousand years demonstrate:

In my own way, I tried to transform the violent aspects of the story so the horrible and violent end of Haman and his ten sons is not a moment for gloating or celebration. This story is, after all, considered part of the sacred canon. While serving as a congregational rabbi, I opened up the narrative to other possible endings when Haman’s plot is revealed. I would ask Nahalat Shalom holy day celebrants, “What shall we do with Haman?” I could count on at least one person to follow the traditional plot line and yell, “Hang him!” But, year after year, the community would slap back with a resounding, “NO!” I would ask again, “So what do we do with Haman?” Many creative responses would ensue! “He should go through a restorative justice program!” “Let him learn how to bake Jewish cookies with Arthur” (a beloved local Jewish baker, z”l). “Let him study our culture.” “Let him do community service.” It was heartwarming to hear that our communal response to the violence in the text was not to glorify it, ignore it, or justify it. Rather, to dismantle it with alternative nonviolent and restorative justice alternatives. In 1994, however, Purim put on a new mask: the mask of zionism. What was once a Jewish carnival holiday became a site for the performance of murderous acts in the name of blotting out the name of Amalek. On Purim 1994, Barukh Goldstein activated his zionist settler world view by entering the Tomb of Abraham in Hebron to literally erase the name of Amalek by fatally shooting 29 Muslim Palestinians in prayer and wounded 130 others with his army issued machine gun before he was overpowered by worshippers. A few years after the massacre, I co-led a Fellowship of Reconciliation delegation (now Eye Witness Palestine) to Hebron/Al Khalil. We visited relatives of the men Baruch Goldstein killed. We sat on small plastic chairs under gray winter skies. The tea could not warm the chill of the stone floor that was the only remnant of the family home. Israel demolished the houses of surviving relatives in the wake of Goldstein’s massacre. to supposedly deter grieving families from retaliating. In addition to making families homeless, Israel further traumatized the Palestinian residents of Hebron by shutting down 1,200 Palestinian market stands and stores along a main thoroughfare called Shuhada Street which, by the way, was repaved with 10 million US tax dollars. Israeli policy has always been aimed at traumatizing Palestinians as a way to force them to leave the country. This is the policy of Israel since 1948 and it has led the Jewish state to accept apartheid as normative to preserve the so-called “Jewish character” of the state. As we approach Purim 2023, Israel is committed now more than ever to ‘finishing’ its project of depopulation of Palestinians. Barukh Goldstein’s most ardent follower holds a key position in the current Israeli government. Itamar Ben-Gvir, a committed Meir Kahane zealot who dresses up as Barukh Goldstein for Purim, believes in annexing the west bank, forced expulsion of Palestinians and apartheid for those who somehow remain. He thinks that birth units in Israeli hospitals should be segregated. 1/3 of Israeli voters cast their ballots for him. He is main stream. Ben-Gvir deploys violence and provocation to incite Palestinians to protest so he can deploy his own specialized police to kill Palestinians, destroy their homes and towns, disappear Palestinian dissidents, and ‘transfer’ Palestinians to Gaza, a virtual prison, or to Jordan. One path to reclaiming the Fast of Esther as a torah of nonviolence is centering Vashti and Esther’s part in the story. The scroll of Esther begins with an act of resistance to patriarchy. Queen Vashti, the king’s chief consort, refuses to obey Ahashverosh’s command to appear before his male companions so he can show off his trophy wife, as it is written, “But Queen Vashti refused to obey the king’s command.” (Scroll of Esther 1:12) Vashti’s noncooperation sets in motion a series of events in the story which culminates in Vashti’s successor also refusing to obey the king’s command. Esther subverts the violent fate ordained by Haman by ordering a public fast in order to bring to light the immanent danger facing Jews. “Go! Gather together all the Jews present in Shushan (and all people who support us). Fast! Do not eat or drink for three days and nights. Those of us in the palace will fast with you in preparation to face the King in non-compliance with his law. If I perish, I perish.” Esther employs fasting as a nonviolent tactic to resist state violence. While the story is fictional, the fast deployed as a call to action has always been a part of our lived tradition. The Fast of Esther is a perfect time for Jews who are committed to universal human rights to use the fast in its traditional context: to give public witness to the immediate violence fasting Palestinians living under Israeli rule and reflect on how we can make a positive difference in ending support for Israel’s occupation that restores equity, dignity and freedom for all of us. “Zachor…Mah Haya Lanu! Remember what happened to us!”

This quote from the liturgy of Tisha B’Av, written in the 12th century by Baruch ben Shmuel of Mainz, expresses how many of us are feeling this season. Tisha B’Av initially commemorated the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE and again in 70 CE, known in Hebrew as Churban HaBayit/Destruction of The House. Over centuries, it expanded to include commemoration of the forced exile of Sefardic Jews from Spain and Portugal, European pogroms, and the Holocaust, initially called Churban before the term Shoah came into use. The Hebrew term Churban denotes catastrophic destruction on a vast scale through human agency. And it is not our historic catastrophes alone we are mourning this year. The deadly set of rulings promulgated by the Supremely right wing Court impacting the bodies and well-being of women, girls and trans people, the sovereignty of Indigenous people, the health of the environment, the lives of Black people, freedom of religion, the right to boycott, and free speech compound the sense of emotional overwhelm present in our communities at this time. How then, might we wield our mourning technologies to meet the needs of the times we live in? From earliest Jewish times, communal mourning also included teshuvah. For instance, we associate the prayer Avinu Malkeinu with the High Holidays, but the Talmud, in tractate Ta’anit (25b) – about public fast days and mourning practices – describes when Rabbi Akiva created it during a drought, i.e. a time of public mourning and repentance. Teshuvah carries the meaning of return to wholeness through acts of repair. In the 12th century, Maimonides famously defined it as a five step process. Here is my updated interpretation of his definition, through a reparations framework: Teshuvah requires acknowledgement of harms (hakarah), remorse (charata) – which, in a reparations framework, is a form of accountability for the harms – and public truth telling of harms by people directly impacted by them. Often, we are tempted to think that is enough, that we feel bad and apologize, but Maimonides argues that is not so. The last two steps – compensation (peira’on) and guarantees of non-repeat of the harm (azivat ha-chet) – are needed for teshuvah reparations to be complete to the satisfaction of injured parties. For the massive harms of colonial settlerism, racism, patriarchy, environmental destruction and, in the Jewish world, Israeli occupation, we need to implement these final two stages. It is not enough to mourn. Mourning must be accompanied by actions that end the harm being done. To what can this be compared? Several years ago I saw Nancy Pelosi wash the feet of migrants who walked the treacherous road from Honduras to the United States to escape violence and climate devastation. As the Speaker of the House washed their feet, she shed tears of sorrow for their plight. In my understanding of faithfulness, however, you can’t wash the feet of traumatized immigrants with one hand and use the other hand to sign off on massive military spending, which is the root cause of the harms that led them to leave their homes in the first place! So it is with us. For the sake of a healed future, we cannot silo our grief from our teshuvah. The two go hand in hand. Humanity’s fate is tied together. This Tisha B’Av, along with the ancient words of Baruch ben Shmuel, I will recite the words of Honduran human rights worker Berta Caceres, who was murdered defending her community’s access to clean water. She said, “In the indigenous world view, we are beings who come from the Earth, from the water, and from corn. Let us wake up! Wake up, humankind! We’re out of time. We must shake our conscience free of the rapacious capitalism, racism and patriarchy that will only assure our own self-destruction… Our Mother Earth, militarized, fenced-in, poisoned, and a place where basic rights are systematically violated, demands that we take action. Let us build societies that are able to coexist in a dignified way, in a way that protects life. Let us come together and remain hopeful as we defend and care for the Earth and all of its spirits and living beings.” Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb is entering her fiftieth year of rabbinic service. She is author of She Who Dwells Within; A World Beyond Borders Passover Haggadah; and Trail Guide to a Torah of Nonviolence. Her newest book, Way of the Mishkan: A Ceremonial Guide to Reparations and Indigenous Land Back Teshuvah will be available this fall, along with her new theater piece, Maggida on Sacred Ground. Lynn lives in Berkeley, California on unceded Ohlone land. She is board chair of Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity and on the rabbinic council of Jewish Voice for Peace. |